Introduction

The question of Jesus’ race—whether he was “Black” or “White”—has sparked intense debate in modern times, often fueled by cultural, political, and social agendas. However, this inquiry imposes contemporary racial categories onto a first-century historical figure, where such distinctions did not exist in the same way. Jesus of Nazareth was a Jewish man born in the region of Judea (modern-day Israel/Palestine) around 4–6 BCE, during the Roman Empire’s rule. Historical records, scientific research on ancient DNA, and biblical references all point to his ethnic background as Levantine or Semitic, with physical traits likely including medium to dark olive skin, dark hair, and dark eyes.[41] Yet, the Bible itself provides no description of his appearance, suggesting that his physical race was irrelevant to his message of love, redemption, and spiritual unity. This article explores the historical, scientific, and biblical evidence surrounding Jesus’ ancestry, while emphasizing why his “race” ultimately does not matter for his teachings or modern worship, especially in light of biblical prohibitions on graven images.

Historical Context of First-Century Judea and Jewish Ethnicity

To understand Jesus’ background, we must examine the historical setting of ancient Judea and Galilee. The Jewish people trace their origins to the ancient Israelites, who emerged in the Levant (the eastern Mediterranean region including modern Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria) around the second millennium BCE as an outgrowth of Canaanite populations.[20][22] By the first century CE, Judea was under Roman control, following periods of Persian, Hellenistic (Greek), and Hasmonean (Jewish) rule. The population was diverse due to trade routes, conquests, and migrations, but Jews maintained a distinct ethnic and religious identity.

Galilee, where Jesus grew up in Nazareth, was a multicultural area with Jewish, Greek, and other Semitic influences, yet archaeological and historical evidence shows it was predominantly Jewish in ethnicity.[21][26] The term “Jew” (Ioudaioi in Greek) referred to people from Judea, encompassing religious, cultural, and ethnic dimensions rather than modern racial lines.[19] Events like the Babylonian exile (587–538 BCE) dispersed Jews to Mesopotamia, introducing some genetic admixture, but returning exiles preserved their Levantine roots.[18] Proximity to Egypt and Africa allowed for interactions, but sub-Saharan influences were minimal in Jewish communities due to geographic barriers and cultural endogamy (marrying within the group).

In this era, “race” was not a biological category but tied to ethnicity and geography. Jesus, as a Galilean Jew, would have appeared similar to other Middle Eastern peoples, not fitting neatly into “Black” or “White” labels.

Scientific and Genetic Evidence on Ancient Jewish Ancestry

Modern genetic studies provide empirical insights into the ancestry of ancient Levantine populations, including Jews. Research on ancient DNA from skeletons in Israel, Jordan, and Lebanon reveals that Bronze and Iron Age inhabitants of the region, including Canaanites, share a strong genetic link with modern Jewish and Arab-speaking populations.[4][7] These studies indicate a core Levantine ancestry, with features typical of Mediterranean and Near Eastern peoples: olive skin tones ranging from light to dark, dark hair, and brown eyes.

For instance, a 2020 study published in Cell analyzed genomes from 73 individuals across five archaeological sites, showing continuity in Levantine genetics over millennia, with minor admixtures from neighboring regions like Iran and Anatolia.[8] Jewish groups, including Ashkenazi Jews, trace much of their ancestry to this ancient Levantine base, with Y-chromosome studies confirming paternal lines from the Near East.[3][0] Palestinians and Jews share over half their ancestry from ancient Canaanites, underscoring a common regional heritage.[6]

Regarding potential African influences, ancient Egyptian genetics show primarily Near Eastern and North African ancestry, with limited sub-Saharan admixture (around 6–15% in later periods due to trade and conquests).[27][29][32] A 2017 study in Nature Communications of 90 Egyptian mummies found they were closer genetically to ancient Near Easterners than modern Egyptians, who have more sub-Saharan DNA from post-Roman migrations.[27] While Egypt’s interactions with Nubia (ancient Cush/Ethiopia) introduced some sub-Saharan genes, these were not dominant in Levantine Jewish populations.[33] Overall, scientific evidence supports Jesus having a mixed but predominantly Levantine genetic profile, defying strict racial binaries.

Biblical References to Ancestry and Intermarriages

The Bible offers genealogical and narrative insights into Jewish ancestry, highlighting intermarriages that could introduce diversity. Jesus’ genealogies in Matthew 1 and Luke 3 trace his lineage through King David to Abraham, emphasizing his Jewish heritage but including non-Israelite women like Rahab (a Canaanite) and Ruth (a Moabite), both from Semitic groups.[17]

King Solomon, an ancestor in Jesus’ line, had 700 wives and 300 concubines, many foreign for political alliances (1 Kings 11:1–3). These included Moabites, Ammonites, Edomites, Sidonians, Hittites, and an Egyptian princess—all from Near Eastern regions, adding minor Semitic and North African admixture but leading to idolatry warnings (1 Kings 11:4–8).[17]

Earlier, Moses married a Cushite woman (Numbers 12:1), interpreted as Ethiopian or Nubian, potentially introducing sub-Saharan ancestry.[9][10][14] Some scholars suggest this was a second wife after Zipporah (a Midianite), and ancient sources like Josephus describe her as an Ethiopian princess.[11][16] However, Moses’ descendants are not directly in Jesus’ Davidic line, and any genetic impact would be diluted over centuries.

These references show biblical allowance for intermarriage under certain conditions (Deuteronomy 7 prohibits Canaanites but not all foreigners), but Jewish law emphasized endogamy to preserve identity (Ezra 9–10).[12] The Bible focuses on faith and covenant, not physical traits.

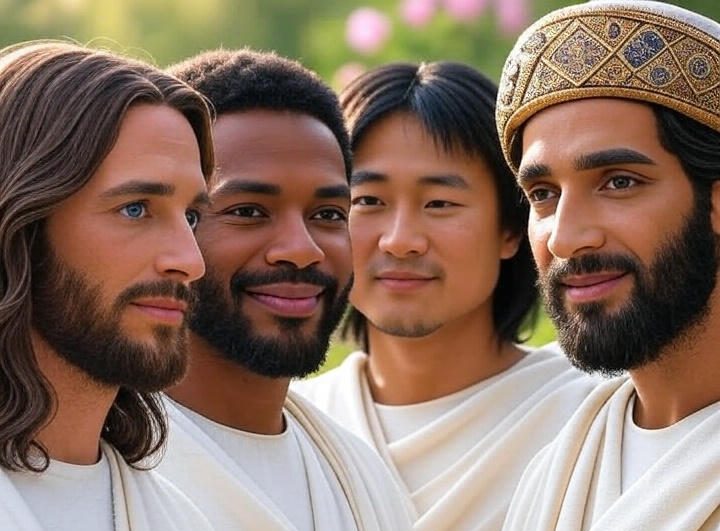

Cultural Depictions of Jesus Across Regions and the Commandment Against Graven Images

Depictions of Jesus have varied widely, reflecting the artist’s cultural context rather than historical accuracy. In early Christian art, he was often shown as a beardless youth or shepherd, evolving into the long-haired, bearded figure in Byzantine icons.[36] By the Middle Ages, European artists portrayed him as White with fair features, influenced by Renaissance ideals and colonial agendas.[40][37] In Africa, Ethiopian Orthodox art shows Jesus with dark skin and African features; in Asia, he appears East Asian; and in Latin America, with Indigenous or Mestizo traits.[36][39][44] These adaptations highlight how cultures relate to Jesus personally, but they also underscore that his race is secondary.[38][43]

However, the Second Commandment (often considered the first in some traditions, as in Jewish numbering) in Exodus 20:4–5 states, “You shall not make for yourself an image in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below. You shall not bow down to them or worship them.” This prohibition against graven images was intended to prevent idolatry, ensuring that worship is directed to God alone, not physical representations.[54] In the context of Jesus, who is considered divine in Christian theology (John 1:1, Colossians 1:15), creating images of him—whether as Black, White, or otherwise—can be seen as risky by some Christian and Jewish interpretations, as it may lead to venerating the image itself rather than the spiritual reality of Christ.[55]

Historically, early Christians debated the use of icons, with some (like the Iconoclasts in the 8th–9th centuries) opposing them, citing the commandment, while others (like the Iconophiles) argued that images of Jesus honor his incarnate nature without being worshipped as idols.[56] Today, many Protestant denominations avoid images of Jesus in worship settings, emphasizing spiritual devotion over physical representation, while Catholic and Orthodox traditions use icons as aids to worship, not objects of worship themselves.[57] The absence of any biblical description of Jesus’ appearance supports the view that images are unnecessary and potentially misleading, reinforcing that his race or likeness is irrelevant to faith.[49]

Theological Views on the Irrelevance of Jesus’ Race

Christian theology emphasizes Jesus’ divinity and humanity over his ethnicity. The New Testament teaches unity in Christ, transcending divisions: “There is neither Jew nor Gentile… for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28).[45][52] His mission was universal, commissioning disciples to reach “all nations” (Matthew 28:19).

Theological reflections argue that obsessing over race distracts from his redemptive work and can perpetuate racism, as seen in critiques of “White Jesus” linked to white supremacy.[51][46][47] Instead, Christianity views humanity through Christ’s lens, rejecting racial hierarchies.[50] The Bible’s silence on his appearance, coupled with the commandment against graven images, reinforces that faith, not phenotype or imagery, is key.[49][53]

Conclusion

Jesus was neither “Black” nor “White” in modern racial terms; he was a Middle Eastern Jew with a genetic heritage reflecting the Levant’s ancient melting pot. Historical contexts, genetic studies, and biblical narratives reveal a complex ancestry with minor admixtures, but these details pale against his timeless message. The Second Commandment’s warning against graven images further underscores that depicting Jesus’ appearance—whether in art or racial debates—risks missing the essence of his teachings. In a divided world, focusing on Jesus’ race or physical likeness distracts from his call for unity beyond earthly categories. As believers, we worship the Christ who unites all humanity, regardless of skin color or image.

Leave a comment